Part 1: Flying into FamePosted May 20, 2015

Amelia Earhart was a pioneer in aviation, which in the early twentieth century was a new and exciting field of technology. The First World War (1914-1918) brought about many innovations as aircraft became effective weapons, but by the 1920s and 30s flight was being explored for many applications beyond the military. As the American fascination with flight grew, it gave rise to a whole generation of aviators competing to set new records and perform outrageous stunts — feats that often made these pilots as rich and famous as today’s Hollywood stars or Top Ten musicians. Earhart said her own interest in flying began when a stunt pilot named Frank Hawks gave her a ride in his airplane. “By the time I had got two or three hundred feet off the ground, I knew I had to fly,” she later said of the experience. |

|

Once her mind was made up, Earhart worked hard to become a flyer. It was difficult because aviation was a field dominated by men in an era when women were not expected to be daring or adventurous. Yet part of the public’s fascination with Earhart had to do with her unconventionality. She wore her hair short, dressed in men’s shirts and trousers, and had an interest in mechanics — all things which were considered “unfeminine” during the 1930s. Earhart was very deliberate in creating this public image, partly because she wanted to inspire other women to break out of social norms and challenge themselves. “Women must try to do things as men have tried,” she said. “When they fail, their failure must be a challenge to others.” |

Destiny Awaits:

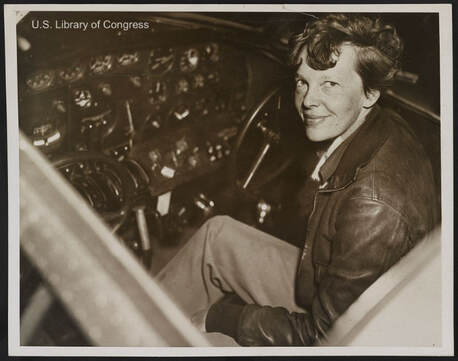

Earhart in the cockpit of her Lockheed Electra.

Earhart in the cockpit of her Lockheed Electra.

By 1937, Earhart had racked up an amazing list of achievements. She was the first person to fly solo from Hawaii to the United States mainland and the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. Now she was ready for her most difficult challenge: to fly around the world as close to the equator as possible. To do this, Earhart needed a highly skilled navigator and chose a man named Fred Noonan. Because much of the trans-world flight would be over the ocean, Noonan’s skills in both marine and celestial navigation would be invaluable.

After one failed attempt in March, Earhart and Noonan set off on their epic journey on May 20, 1937 aboard their specially-modified Lockheed Electra airplane. For the next six weeks, people from all over the world followed their progress in the newspapers and on newsreels shown in local theaters. By July 2, the duo had reached the Territory of New Guinea (today known as Papua New Guinea) and were preparing for the longest and most dangerous leg of their trip. Their challenge was to fly east across the vast South Pacific Ocean to tiny Howland Island over 2,500 miles (4,023 km) away. Because the distance was so far, there was little room for error or the Electra would run out of fuel and crash into the ocean. To help her find the island, the United States Coast Guard had positioned a ship called the Itasca nearby which would help guide Earhart in through radio navigation. But then something went terribly wrong, the details of which are still controversial. Whether the problems came from flight crew errors, equipment failure, poor planning or just bad luck, it was obvious to the crew aboard the Itasca that Earhart could not hear their radio transmissions nor find not find them or Howland Island. The Coast Guard personnel frantically tried to raise the aviatrix on the radio, but she was not able to hear them due to a broken antennae on the aircraft. As time and the Electra’s fuel began to dwindle, Earhart’s radio messages became more and more frantic.

Her last transmission was simply: "We are running on line north and south.”

After one failed attempt in March, Earhart and Noonan set off on their epic journey on May 20, 1937 aboard their specially-modified Lockheed Electra airplane. For the next six weeks, people from all over the world followed their progress in the newspapers and on newsreels shown in local theaters. By July 2, the duo had reached the Territory of New Guinea (today known as Papua New Guinea) and were preparing for the longest and most dangerous leg of their trip. Their challenge was to fly east across the vast South Pacific Ocean to tiny Howland Island over 2,500 miles (4,023 km) away. Because the distance was so far, there was little room for error or the Electra would run out of fuel and crash into the ocean. To help her find the island, the United States Coast Guard had positioned a ship called the Itasca nearby which would help guide Earhart in through radio navigation. But then something went terribly wrong, the details of which are still controversial. Whether the problems came from flight crew errors, equipment failure, poor planning or just bad luck, it was obvious to the crew aboard the Itasca that Earhart could not hear their radio transmissions nor find not find them or Howland Island. The Coast Guard personnel frantically tried to raise the aviatrix on the radio, but she was not able to hear them due to a broken antennae on the aircraft. As time and the Electra’s fuel began to dwindle, Earhart’s radio messages became more and more frantic.

Her last transmission was simply: "We are running on line north and south.”

The Search That Failed

Within an hour of Amelia being declared overdue, the Itasca was circling the waters around Howland Island in a search of the aircraft. Within a few days, many other ships and aircraft would join in as the world held its breath hoping that Earhart and Noonan would be found alive. Most of the rescue efforts centered around the belief that the Electra had crashed at sea. But did it? The last transmission regarding the plane flying along a line “north to south” might have meant that Earhart turned to the south when she couldn’t find Howland Island. To many investigators, this made logical sense. Both Earhart and Noonan knew that there were numerous islands to the south which might provide them with a place to land.

Within a week of the disappearance, US Navy aircraft buzzed over the Phoenix Island chain and provided an aerial survey of an uninhabited atoll called Gardener Island (today known as Nikumaroro). The participating pilots reported “signs of recent habitation” but no one ever followed up with a ground search. Gardener Island was removed from the list of possible crash sites and the search refocused on the open ocean.

By July 19, the navy and coast guard called it quits without finding a single scrap of evidence as to Earhart and Noonan’s fate. Two years later, the aviators were declared legally dead but the strange circumstances around their disappearance, combined with the lack of physical evidence to prove they crashed into the sea, would continue to nag at investigators for decades to come.

Images: U.S. Library of Congress

Within a week of the disappearance, US Navy aircraft buzzed over the Phoenix Island chain and provided an aerial survey of an uninhabited atoll called Gardener Island (today known as Nikumaroro). The participating pilots reported “signs of recent habitation” but no one ever followed up with a ground search. Gardener Island was removed from the list of possible crash sites and the search refocused on the open ocean.

By July 19, the navy and coast guard called it quits without finding a single scrap of evidence as to Earhart and Noonan’s fate. Two years later, the aviators were declared legally dead but the strange circumstances around their disappearance, combined with the lack of physical evidence to prove they crashed into the sea, would continue to nag at investigators for decades to come.

Images: U.S. Library of Congress