Navigate:VIRTUAL EXPLORATIONS > ARCHIVED EXPLORATIONS > CREEP INTO THE DEEP 2015

|

Part 6: Life on a Research ShipGuest Contributor: Dr. Edith Widder, Marine Biologist and Deep-sea Explorer

Posted July 23, 2015: The seas are glassy smooth and the sky is clear. I haven’t seen any dolphins yet but I spend so much time in the ROV shack during the day I wouldn’t have much opportunity to spot them if they are out there. There is very little “down time” but when there is the primary leisure pursuits are reading, watching TV and playing cards. For me the best fun is watching the ROV dive and trading jokes with the pilots and other scientists. |

Of course, since we’re in the middle of the ocean we live on the ship during the research cruise. We’re on the Pelican, which is a smaller research ship. It is almost three school buses long. If it tried to park at your house, it wouldn’t fit in your driveway. But as far as ships go, it’s smaller. However, it has it has nice space for our labs and that’s what we need on a research cruise like this.

We share cabins with other folks in the science team. The bunks beds are on the small side. The bunks on this ship might be the smallest I’ve ever slept in. The bunk above me is so close that I sometimes bump against it when I’m turning over at night. Tammy and I share a two berth cabin while Heather, Mackey, Brenna and Katie share a four berth cabin. The 6 of us women share one head (that’s the what you call the bathroom on a ship). The head consists of one sink, one toilet and one shower.

The mess, where we eat, is comfortable and the food is good. Just now for lunch, we had Shepherd’s pie and salad. There are plenty of snacks for between meal grazing — both healthy (fruit and raw vegies) and not (chips and candy). The freezer is packed with every kind of ice cream — that I’m trying to stay away from! Between meals, the mess is a great place to work and socialize.

What we wear depends on whether we’re working out on deck or in the lab.

Outside is baking hot and is usually best managed with shorts and a thin long sleeve shirt to keep the sun off or a tank top and lots of sun screen. Inside it is heavily air conditioned to keep the equipment happy if not always the people. The ROV shack in particular has a lot of important computers and equipment and is kept especially chilly, which means we need to bundle up in long pants and hoodies when we’re in there watching a dive.

Speaking of watching the dives, I better get back to the ROV Shack!

Related Features: Studying at Sea

Photos courtesy of Dr. Edith Widder.

We share cabins with other folks in the science team. The bunks beds are on the small side. The bunks on this ship might be the smallest I’ve ever slept in. The bunk above me is so close that I sometimes bump against it when I’m turning over at night. Tammy and I share a two berth cabin while Heather, Mackey, Brenna and Katie share a four berth cabin. The 6 of us women share one head (that’s the what you call the bathroom on a ship). The head consists of one sink, one toilet and one shower.

The mess, where we eat, is comfortable and the food is good. Just now for lunch, we had Shepherd’s pie and salad. There are plenty of snacks for between meal grazing — both healthy (fruit and raw vegies) and not (chips and candy). The freezer is packed with every kind of ice cream — that I’m trying to stay away from! Between meals, the mess is a great place to work and socialize.

What we wear depends on whether we’re working out on deck or in the lab.

Outside is baking hot and is usually best managed with shorts and a thin long sleeve shirt to keep the sun off or a tank top and lots of sun screen. Inside it is heavily air conditioned to keep the equipment happy if not always the people. The ROV shack in particular has a lot of important computers and equipment and is kept especially chilly, which means we need to bundle up in long pants and hoodies when we’re in there watching a dive.

Speaking of watching the dives, I better get back to the ROV Shack!

Related Features: Studying at Sea

Photos courtesy of Dr. Edith Widder.

Related Oceanscape Features:

Destiny Awaits:

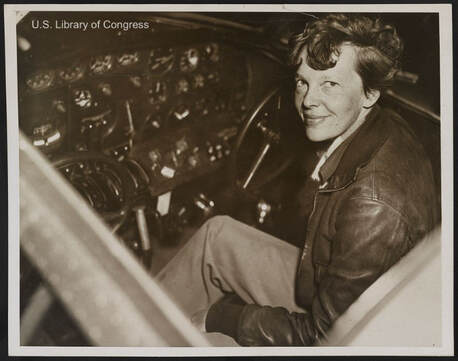

Earhart in the cockpit of her Lockheed Electra.

Earhart in the cockpit of her Lockheed Electra.

By 1937, Earhart had racked up an amazing list of achievements. She was the first person to fly solo from Hawaii to the United States mainland and the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. Now she was ready for her most difficult challenge: to fly around the world as close to the equator as possible. To do this, Earhart needed a highly skilled navigator and chose a man named Fred Noonan. Because much of the trans-world flight would be over the ocean, Noonan’s skills in both marine and celestial navigation would be invaluable.

After one failed attempt in March, Earhart and Noonan set off on their epic journey on May 20, 1937 aboard their specially-modified Lockheed Electra airplane. For the next six weeks, people from all over the world followed their progress in the newspapers and on newsreels shown in local theaters. By July 2, the duo had reached the Territory of New Guinea (today known as Papua New Guinea) and were preparing for the longest and most dangerous leg of their trip. Their challenge was to fly east across the vast South Pacific Ocean to tiny Howland Island over 2,500 miles (4,023 km) away. Because the distance was so far, there was little room for error or the Electra would run out of fuel and crash into the ocean. To help her find the island, the United States Coast Guard had positioned a ship called the Itasca nearby which would help guide Earhart in through radio navigation. But then something went terribly wrong, the details of which are still controversial. Whether the problems came from flight crew errors, equipment failure, poor planning or just bad luck, it was obvious to the crew aboard the Itasca that Earhart could not hear their radio transmissions nor find not find them or Howland Island. The Coast Guard personnel frantically tried to raise the aviatrix on the radio, but she was not able to hear them due to a broken antennae on the aircraft. As time and the Electra’s fuel began to dwindle, Earhart’s radio messages became more and more frantic.

Her last transmission was simply: "We are running on line north and south.”

After one failed attempt in March, Earhart and Noonan set off on their epic journey on May 20, 1937 aboard their specially-modified Lockheed Electra airplane. For the next six weeks, people from all over the world followed their progress in the newspapers and on newsreels shown in local theaters. By July 2, the duo had reached the Territory of New Guinea (today known as Papua New Guinea) and were preparing for the longest and most dangerous leg of their trip. Their challenge was to fly east across the vast South Pacific Ocean to tiny Howland Island over 2,500 miles (4,023 km) away. Because the distance was so far, there was little room for error or the Electra would run out of fuel and crash into the ocean. To help her find the island, the United States Coast Guard had positioned a ship called the Itasca nearby which would help guide Earhart in through radio navigation. But then something went terribly wrong, the details of which are still controversial. Whether the problems came from flight crew errors, equipment failure, poor planning or just bad luck, it was obvious to the crew aboard the Itasca that Earhart could not hear their radio transmissions nor find not find them or Howland Island. The Coast Guard personnel frantically tried to raise the aviatrix on the radio, but she was not able to hear them due to a broken antennae on the aircraft. As time and the Electra’s fuel began to dwindle, Earhart’s radio messages became more and more frantic.

Her last transmission was simply: "We are running on line north and south.”

The Search That Failed

Within an hour of Amelia being declared overdue, the Itasca was circling the waters around Howland Island in a search of the aircraft. Within a few days, many other ships and aircraft would join in as the world held its breath hoping that Earhart and Noonan would be found alive. Most of the rescue efforts centered around the belief that the Electra had crashed at sea. But did it? The last transmission regarding the plane flying along a line “north to south” might have meant that Earhart turned to the south when she couldn’t find Howland Island. To many investigators, this made logical sense. Both Earhart and Noonan knew that there were numerous islands to the south which might provide them with a place to land.

Within a week of the disappearance, US Navy aircraft buzzed over the Phoenix Island chain and provided an aerial survey of an uninhabited atoll called Gardener Island (today known as Nikumaroro). The participating pilots reported “signs of recent habitation” but no one ever followed up with a ground search. Gardener Island was removed from the list of possible crash sites and the search refocused on the open ocean.

By July 19, the navy and coast guard called it quits without finding a single scrap of evidence as to Earhart and Noonan’s fate. Two years later, the aviators were declared legally dead but the strange circumstances around their disappearance, combined with the lack of physical evidence to prove they crashed into the sea, would continue to nag at investigators for decades to come.

Images: U.S. Library of Congress

Within a week of the disappearance, US Navy aircraft buzzed over the Phoenix Island chain and provided an aerial survey of an uninhabited atoll called Gardener Island (today known as Nikumaroro). The participating pilots reported “signs of recent habitation” but no one ever followed up with a ground search. Gardener Island was removed from the list of possible crash sites and the search refocused on the open ocean.

By July 19, the navy and coast guard called it quits without finding a single scrap of evidence as to Earhart and Noonan’s fate. Two years later, the aviators were declared legally dead but the strange circumstances around their disappearance, combined with the lack of physical evidence to prove they crashed into the sea, would continue to nag at investigators for decades to come.

Images: U.S. Library of Congress